Nation’s first communal dialysis home in Hāna needs repairs to keep operating at full capacity

HĀNA — When Cece Park first started dialysis in 2005, she and her husband Andrew would get up in the middle of the night, pack a chainsaw in their truck for fallen trees, and make the winding two-hour drive from Hāna to Wailuku on a roadway known for landslides and rainstorms in order to make her 4 a.m. appointment.

She chose a slot at the crack of dawn so she could finish her session of three and a half hours and make the long drive back as early as possible, a routine the Parks repeated three times a week for several years.

Dialysis patients living in the remote East Maui community had few other options at the time. Missing the critical treatments, which clean out waste from the blood when a patient’s kidneys are failing, is dangerous and could lead to heart problems and death, according to the National Kidney Foundation.

But Lehua Cosma, the Parks’ daughter, was just as concerned about her parents and other patients making the thrice-weekly journey.

“The long trips to the other side really took a toll on their health and their well-being,” she said. “Some gave up treatment.”

Sixteen years ago, Cosma’s pleas to government officials helped turn a former county physician’s home on the outskirts of Hāna town into the first communal home dialysis center in the country. Hale Pōmaika‘i has allowed patients like her mom to receive treatment much closer to home.

But now the aging, four-bedroom, 1,500-square-foot home is in need of fumigation and repairs, with termites eating into the wood and the front bedroom sagging. Treatments can no longer take place in the front bedroom, and the three patients — two women and one man ranging in age from their late 50s to their 70s — have been using the other three rooms.

Maui County, which owns the home and leases it to the nonprofit Hui Laulima O Hāna led by Cosma, plans to provide funding to help with the repairs.

Cosma and Madge Schaefer, the dialysis home’s former project manager, say they’re trying to do everything they can to keep the patients from having to drive to Central Maui again for treatment.

“The house has been a lifesaver for those Hāna residents and we just need to do it quick,” Schaefer said.

ONLY A MATTER OF TIME

When dialysis home staff first noticed the cracks in the front bedroom about a month ago, Cosma called Rick Rutiz. The retired founder of Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike, a youth vocational training program, had brought a crew to build a handicap-accessible ramp and spruce up the interior when it first opened in April 2009.

Rutiz crawled underneath the home and poked at the wood. The house had been built upon uneven rocks instead of more modern pier blocks and was starting to sink into the stones. But “that’s not what’s making it tilt,” he said. “It’s more the termite damage and the dry rot.”

In the front bedroom, growing cracks are visible in the top and bottom corners of the room. The window frame is crooked in places. The slant in the floorboards is palpable.

The house doesn’t need to be torn down, but the front bedroom needs to be fixed, and the home needs to be fumigated, Rutiz said. A nearby gunpowder tree — named for the gunshot-like sound its branches make when it falls — also needs to be removed because the roots are poking through the pavement fronting the house and it’s causing mildew on a shaded section of the home.

Rutiz emphasized the house needs to stay intact for the sake of the community, saying: “It’s still safe, and it serves a very important purpose.”

The property also includes a two-bedroom cottage for additional patients.

Hui Laulima O Hāna met with Maui County Mayor Richard Bissen, Director of Human Concerns Lori Tsuhako and other county officials near the end of October to discuss the situation.

The lease makes it clear that the nonprofit is responsible for the upkeep and maintenance of their property, which is “a standard sort of language in our leases,” Tsuhako said.

But, “the challenge is that this is a very, very small organization” with limited funding and a staff of four. Maui County pays the hui a grant of about $130,000 to operate the dialysis home, but that’s “not a lot of money that can be set aside to put into repair and maintenance,” Tsuhako said. Those funds go toward costs like the two technicians’ salaries, utilities and insurance, Cosma said.

Tsuhako said the department has $100,000 in funding that could help pay for fumigation and repairs, but the county has to wait and see how much the repairs will cost. An estimate is expected next week.

Claire Kamalu Carroll, a Hāna resident and office manager for the Maui County Business Resource Center, has been calling up contractors to get quotes and said one company offered to do the termite tenting at $5,000. They’re waiting on an estimate from the contractor who plans to fix the bedroom.

Carroll said she is recusing herself from looking into tree removal companies because her son operates one in Hāna. Schaefer said they got an initial quote of about $12,000 to remove the tree.

While the work is ongoing, “we collectively as the county will do everything we can to try and reduce the burden on the patients and their families,” Tsuhako said.

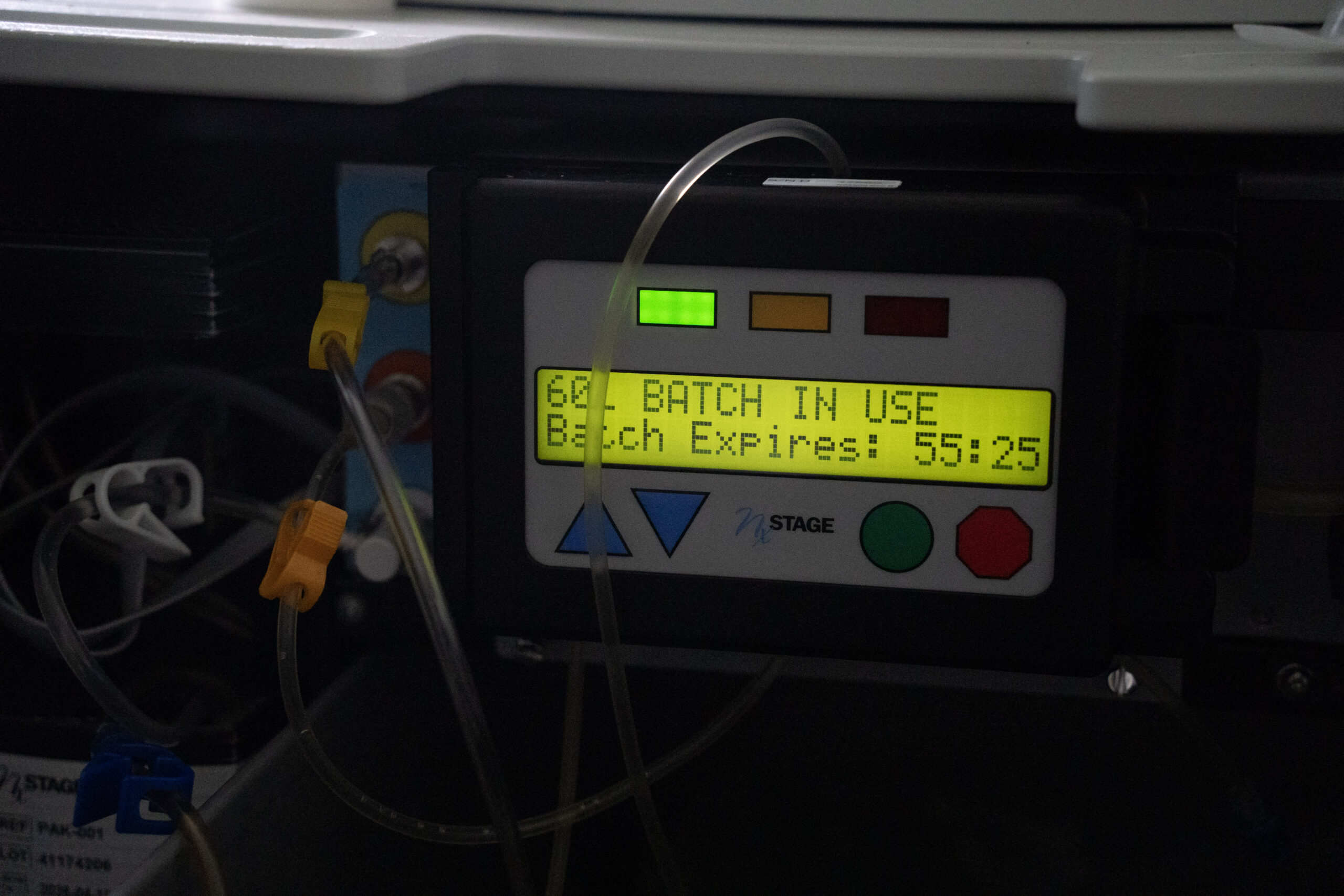

However, the solution is not as simple as moving the machines into patients’ homes. The plumbing and electrical system in the dialysis home had to be upgraded to handle the requirements of the machines, and each machine has its own drain, Schaefer said. Most homes are not equipped for the full setup of hoses, wires and the volume of water that needs to be filled and drained.

“We’re hoping that whatever they do, they can do it in phases so that the patients could continue to receive treatments at the house safely,” Schaefer said.

The goal is to get the repairs done by the end of the year, and Schaefer said they hope to block off the dilapidated front bedroom so contractors can work on it while patients continue treatment in the back rooms. They also plan to schedule fumigation on a day when the patients aren’t coming in.

However, if the patients do have to leave the house, Cosma said the plan is to have them get treatment at Fresenius Medical Care, which offers dialysis services in Maui Lani and Kahana and supplies the Hāna home with machines.

TAXING TREATMENT

No one wants to add a longer commute for patients already undergoing exhausting dialysis treatment.

“It is taxing on your body because if you think about it, your kidney works 24 hours a day, so when you’re having dialysis only three days a week, that constitutes … maybe 15% of what a kidney function would do,” explained Joy Carvalho, charge nurse with Fresenius Medical Care.

The dialysis machines used in the Hāna home are gentler on the body than the ones in the clinic because they’re removing fluids more slowly over a longer period of time — four days as compared to three.

In Hawai‘i, the number of people living with kidney failure has increased 61% since 2011, according to the American Kidney Fund. In 2024, a total of 6,048 people were living with kidney failure, with 5,063 on dialysis.

Nationwide, about 815,000 Americans are living with kidney failure, and nearly 555,000 are on dialysis, the American Kidney Fund reported.

The number of patients at the Hāna dialysis home may be few, but the service is vital in a town with one main clinic — Hāna Health, a private nonprofit — and a two-hour commute to the island’s only acute-care hospital, Maui Memorial Medical Center.

When Cosma first started thinking about how she could make it easier for her mom to get dialysis, she talked with Dr. Steven Moser, a local nephrologist who saw patients in Hāna twice a month. But when he unexpectedly died in his sleep in March 2005, Cosma “felt so lost, because he was spearheading this.”

“I didn’t know what else to turn to,” Cosma said.

That’s when she heard about an advisory committee appointed by then-Gov. Linda Lingle to hear concerns on different islands. Schaefer was the chair, and when they held a meeting on Maui, Cosma shared the story of her parents’ grueling journey. The committee said they would look into it.

“I knew exactly what she was talking about,” said Schaefer, whose father had been on dialysis after contracting sepsis.

They set their sights on an old plantation home in Hāna that a 1927 executive order by Hawai‘i’s territorial governor had set aside for a Maui County physician. That was no longer the case; the doctor there worked for Hāna Health. But getting permission to convert the home was a complicated task — the state owned the land, the county owned the home, and the federal government needed to approve a home dialysis facility.

The local governments were supportive. In January 2009, the state Board of Land and Natural Resources backed the use of the .85-acre property for “health and safety programs,” the Honolulu Advertiser reported at the time. In February 2009, Lingle cancelled the 1927 executive order, and that same month, the Maui County Council voted to lease the property to the hui for 20 years at a rate of $1 a year.

Medicare officials were the only ones on the fence. Schaefer, Cosma and the dialysis patients kept bugging them.

“You folks think easy what we gotta go through,” Cosma recalled Lono saying. “You go drive that road. You come back. You tell me.”

Finally, while at a conference in Honolulu, a Medicare official decided to fly to Maui, rent a car and drive to Hāna on his own. Both Cosma and Schaefer recall the ill-fated drive, which reportedly ended near Kailua, in the pouring rain, with the official throwing up.

“He turns around and goes back and calls me and says, ‘OK.’ That’s how we got the approval,” Schaefer said.

Once they got the home, preparing it for patients was “a real community effort,” said Schaefer, who became the project manager.

Rutiz would call with a wish list of supplies, and a volunteer with a pickup truck would load them up at Home Depot and bring them to Hāna. Someone tracked down a brand-new, unused generator that they bought for a discounted price. Cosma still remembers how Schaefer and her husband came all the way from Kīhei to help put up wallpaper and install the fans.

When the home opened in April 2009, Cece Park and Francis “Uncle Blue” Lono were the first patients.

“She was so happy,” Cosma said of her mother. “She said, ‘I never thought (my) dream would come true.’”

Cosma told her mom to pick a room. She chose the front bedroom, because she could see all the cars passing by. While she was getting the life-saving treatment, Cosma’s dad stayed busy cleaning the yard or cooking up the fish he’d caught for the patients’ lunch. The smell of frying fish would waft through the home as the hungry patients emerged from their treatments.

Cosma spent many hours in the front bedroom while her mom went through dialysis. Her mom was in so much pain, but she tried not to show it in front of the staff.

“She just played tough,” Cosma said. “She always was smiling.”

Her mom died in December 2009, after a fall in the bathtub flared up an old tailbone injury from her days of horseback-riding and she contracted sepsis in the hospital. Afterwards, Cosma would go into the front bedroom where she used to get dialysis and hang out there, because it still smelled like her.

“It took about a month before I really got over it,” she said. “But it made me stronger and wiser, to never give up and fight for what we need.”

Cosma said Uncle Blue, the other patient, was “a living testament of how long you can live with dialysis.”

His younger sister Alice Kai said her brother was happy to stay in Hāna and not have to take the bus to Central Maui three times a week.

Doctors told Lono he’d only had about seven more years to live. He outlasted that by eight years, dying in 2015.

“Only he knows, only God,” Kai said. “And I guess my brother was strong.”

Schaefer remembers the morning Cosma called her and said, “I want to tell you about Uncle Blue.” Schaefer braced for bad news but got the opposite. His wife had woken up and found he wasn’t in bed, so she went to the kitchen and found he’d made coffee, something he hadn’t been well enough to do in years.

“It all comes down to how you care for people,” Cosma said. “It was home, near his family, and he looked forward to treatment because the girls that take care of him would make him laugh.”

Cosma and the hui have done what they can to make the home as comfortable an experience as possible. There’s a hospital recliner in each of the four bedrooms, and they’re all equipped with TVs to keep the patients entertained during sessions.

Sometimes Cosma brings them musubi or manapua, “just the small treats. Oh, you see their face light up.” Some patients live off the grid with no electricity or freezers, and they have kūpuna meals delivered to the dialysis home. The staff will heat up the food in the microwave before they go home and keep the extras in the freezer for them.

There’s a thrift store on site, affectionately called the “Hana Macy’s,” where people can give monetary donations in exchange for clothes, glassware, books and old Hawaiian music cassette tapes. Cosma said they tap into donations to cover shortfalls when needed.

The dialysis home’s mission is personal for the close-knit community. Before it opened, Carroll remembers her dad, former Maui County Council Member Bob Carroll, driving Lono into town for treatments. The most recent dialysis patient to pass away was a cousin of hers.

“These are friends and family,” she said. “… We cannot lose our dialysis center. I mean, I’ll try any means to always keep it up and running.”

Schaefer pointed out that folks on dialysis can still live full lives. After their treatment, “they go back to their regular jobs and their regular functioning. It’s not a handicap.”

Keeping the dialysis home going was Cece Park’s last wish. In December 2009, on the night before she died, she called her daughter one last time from Maui Memorial.

“Please, promise me something,” she told Cosma. “Always make sure the dialysis is here. Don’t give up. There’s many more going to need it.”

When Cosma was born, her mom had to go to Wailuku to give birth because of complications during her pregnancy. That’s why you turned out so hard-headed, she told Cosma, the oldest of her seven children. But that stubborn streak came in handy when Cosma lobbied for the dialysis home, and she’ll need it again to tackle the latest obstacles.

“I just feel like I have to carry on her legacy,” Cosma said. “I made a promise.”