Group that saved Honolua Bay from development now wants it to become a cultural sanctuary with fewer tourists

HONOLUA BAY — Paele Kiakona used to dread driving past the crowds of cars and tourists at Honolua Bay on his drive home to Honokōhau Valley.

But after the August 2023 wildfire devastated Lahaina and visitors disappeared, he took a trip down to the bay to soak in the surroundings as the waves washed up on the rocky shoreline.

“That in itself brought healing to me. … And I was only able to see that because there was nobody there,” said Kiakona, who is now vice president of the nonprofit Save Honolua Coalition.

With its coral reefs and big winter swells, Honolua Bay is one of the biggest draws in West Maui, bringing in anywhere from 500 people on a slow day to 1,000 on a busy day, according to Heidi Beltz, coordinator of the coalition’s Makai Watch program.

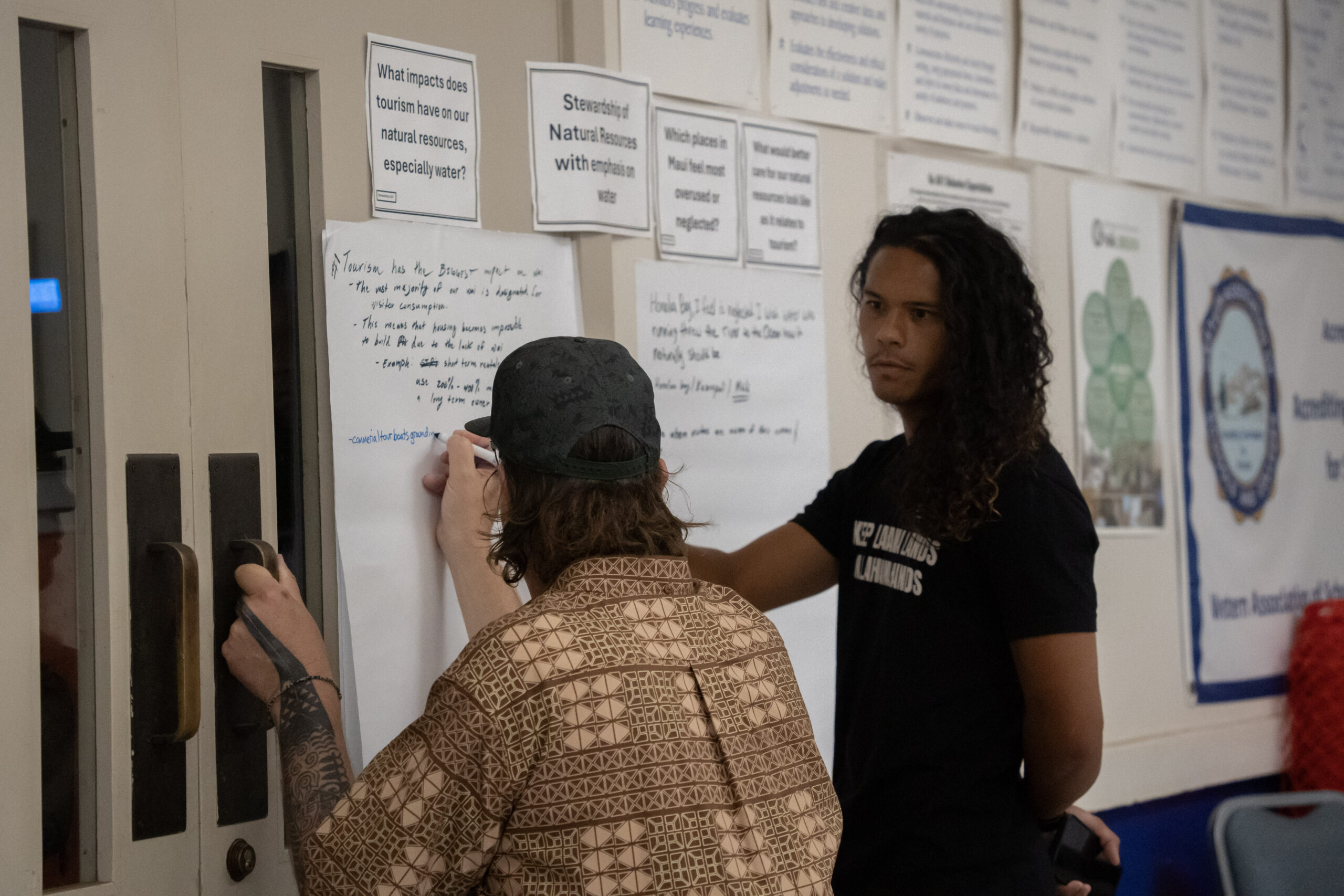

The coalition was created in the early 2000s to stop construction of a luxury development and golf course on the hills above Honolua Bay. Now, the group wants to work with the state to reduce the number of tourists by two-thirds and turn a portion of the area into “Pu‘uhonua o Honolua,” a cultural sanctuary set aside for traditional practices and education.

“Honolua has a profound ability to fill people’s cups, and our community needs that,” said John Carty, a founding member of Save Honolua.

The state Department of Land and Natural Resources, which acquired the land surrounding the bay from Maui Land & Pineapple Co. a decade ago, says the community’s plans are a good start and could follow the success of management programs at other Hawai‘i hotspots.

“The main thing has been achieved: resort development was stopped, open space has been preserved, and it’s now locked in for no more development,” said Curt Cottrell, state parks administrator. “But now it’s a question of, how do you manage human use?”

PROTECTING HONOLUA’S HISTORY

The first day that Beltz was stationed at Honolua Bay to educate visitors, she ran across a woman taking nude photos in the forest.

Photoshoots are among the many things that beachgoers are asked not to do in signs posted along the dirt path leading down to the bay. The signs, a combination of handpainted community pleas and official state rules, ask people to stay on the trail to avoid unmarked graves, pick up their trash, use reef-safe sunscreen and avoid going to the bathroom in the bushes.

There’s a reason for all the rules. Honolua Bay is a sensitive historic and cultural site. Kamehameha I, after conquering Maui in 1790, bestowed the ahupua‘a of Honolua and Honokahua to Kamehameha II, according to the Department of Land and Natural Resources. It’s home to burials and heiau (places of worship) and served as an important fishing ground for kānaka maoli (native Hawaiians).

In 1976, the famed voyaging canoe Hōkūle‘a departed Honolua Bay on her maiden journey to Tahiti, one of the catalysts for a period of revival for Hawaiian language and traditional practices.

“That bay has the importance of sparking the Hawai‘i Renaissance, reinvigorating our identity as a people here,” Kiakona said. “So that’s how important that is to us.”

In 2007, then-landowners Maui Land & Pineapple Co. proposed a development of 40 luxury homes and a golf course at Līpoa Point, an area overlooking the bay that was named for the limu līpoa that kānaka maoli gathered to feed their families.

Save Honolua and other community groups rallied to stop the development and lobbied the state for years to protect the land. In 2013, lawmakers passed a bill that allowed the state to purchase nearly 250 acres at Līpoa Point for $19.5 million in 2014.

“The sheer rapture of having that kind of victory … I mean, I could have won $15 million and it wouldn’t have felt any better than that,” said Carty, who’s lived in the area for nearly 25 years.

Since then, the state has spent years making plans for the area, creating a scoping report in 2018 that led to a draft version of a Honolua to Honokōhau Management Plan in 2024. Cottrell said they are nearing the release of a final version.

Earlier this month, Save Honolua unveiled its own management plans, driven in part by a series of recent groundings at Honolua Bay, including a 94-foot luxury yacht that ran aground in 2023 and a 65-foot catamaran that washed up on the rocks in January. The groundings and the damage to the reef “woke us up and we got really focused really quickly,” Carty said.

The coalition modeled its plan after Hā‘ena State Park on Kaua‘i, where overcrowding and illegal parking created safety hazards and impacted fragile resources. The community and the state created a management plan and reduced visitor counts from 2,000 to 3,000 a day to an average of 700.

Save Honolua wants to reduce tourism at Honolua by two-thirds by creating a visitor reservation system and an offsite parking lot and shuttle system like the one used at Hā‘ena. Limited on-site parking would be reserved primarily for kama‘āina, with most visitors parking in a designated lot mauka of Līpoa Point, according to the plan.

The plan envisions a dedicated entrance for kama‘āina and cultural practitioners and spaces that include a living classroom for keiki, a hale wa‘a or traditional canoe house, a hale ho‘ōla for healing arts such as lomilomi massage, and a community hale for gathering, teaching and events.

Save Honolua hopes to acquire just under 20 acres from Maui Land & Pine to use for the cultural sanctuary. Carty declined to provide a cost because negotiations are ongoing.

A top priority is to identify burials with ground-penetrating radar. The plan estimates there are over 700 known ancestral burials and sacred sites in the area.

Out on the water, the coalition wants two of the bay’s three moorings to be set aside for Hōkūle‘a and the Maui voyaging canoe Mo‘okiha O Pi‘ilani, and leave the third for snorkel tour boats. Kiakona said Hōkūle‘a has to compete with tour boats for moorings, and Mo‘okiha O Pi‘ilani hasn’t had a permanent home since the fire.

The plan also proposes a governing council of lineal descendants and cultural practitioners with decision-making power for the sanctuary. Kapu (forbidden) periods could also be instituted with closures of Honolua’s trails and the bay to allow “nature to rest.”

Denver Coon, an owner of Trilogy Excursions and president of the Ocean Tourism Coalition, said “there’s no doubt there’s disruptions” to the environment from visitors traversing the area. But he said the advantages of bringing in people by boat is that they stay off the trails and can use the bathroom on board.

Honolua Bay’s big winter swells already keep out boats “for a significant portion of the year,” Coon pointed out. Limiting commercial operators to one mooring would be “incredibly difficult” because there’s a short window during the day when the weather is good for sailing there. And, they’d have to decide “who’s in and who’s out” among the Kāʻanapali and Lahaina tour operators.

Trilogy has been running tours to Honolua for 40 years and is still recovering from the fire that destroyed one of its catamarans. Coon said they’ve always been willing to adjust their schedule when there are major events at the bay. But if their window grows more limited, they will start to lose days and this will start impacting their operations, which are already down 40% since the fire.

He hopes the community and commercial operators can work together on a vision for Honolua.

“The good thing about living on an island is we typically try to come to some type of consensus and try to reach some type of solution that’s a balanced approach,” he said.

Cottrell said that Save Honolua’s proposal to control visitor numbers and parking is “totally in the wheelhouse.” The plan would likely become more feasible if the coalition can secure the land adjacent to the state’s.

Save Honolua could also use parking fees to help fund management costs. At Hā‘ena, the State Parks Division collects the revenue from entry fees, but the community group Hui Maka‘āinana o Makana keeps the parking revenue. Only 10 of Hawai‘i’s 54 state parks charge for parking and entry, but those parks — including ʻĪao Valley, Wai‘ānapanapa and Mākena on Maui — help cover costs for other parks that don’t have as many visitors. It’s enough to allow the state to share revenue with nonprofits.

“We need management, and so it’s like we’re outsourcing the management to people that are from that ‘āina, and it’s a perfect opportunity for the Save Honolua guys to do what we’ve done at Hā‘ena,” Cottrell said.

Cottrell agrees it’s taken a long time to move forward with plans at Honolua. The challenge is that the state took over the land “without any additional funding, bodies, management capacity, law enforcement” necessary to oversee the area.

And, it’s been tough to get consensus on issues like parking. Surfers don’t want to see the dirt overlook above Honolua Bay become a paved parking lot.

“It’s taken the state a long time partially because this is a very complicated acquisition to figure out how to put a management bubble on and have it all work,” Cottrell said.

A BETTER BALANCE

Kevin Daproza, a Lahaina resident whose family recently moved into their newly rebuilt home, said he and his family usually avoid Honolua in the summer because there are too many tourists.

“Any given day in the summer there’s like a hundred people out” in the water brought by tour companies, he said.

On Thursday, a slower day during the shoulder season, he took his 10-year-old son Greyson and fellow groms Avin Coon, 11, and Maverick Wheeler, 10, down to Honolua for an afternoon of surfing. Daproza said he supported efforts to better manage a place that he described as a “crown jewel of surf spots.”

“We need some kind of infrastructure, some kind of management, just so that someone has the responsibility to take care of it,” he said.

A group of hostel workers who recently moved to Pā‘ia were enjoying an afternoon of snorkeling on Thursday. They said the colors of Honolua’s reef are a stark contrast to the bleached coral seen in other places, and they supported the idea of reducing the number of visitors.

“Whenever someone says that, I think people will get all up in arms because they want to come and experience it, but I think it’s also a privilege and an honor to come and experience that,” Emily Avery said. “And if you need to do that in order to preserve something as beautiful as this, then I think you should be able to do what needs to be done.”

Sne Patel, president of the LahainaTown Action Committee, said the question of balancing tourism’s economic boosts with it’s impacts has “always been a struggle.” But since the fire, overtourism hasn’t been the problem — it’s the lack thereof, he said. Businesses are struggling to stay afloat as they wait for Lahaina to rebuild, and the community needs the jobs so people can stay in West Maui.

He said he supports better management of Honolua that prioritizes resident access and stewardship, but that the ideal capacity should be determined before limits are put on anything.

“One thing’s for sure: if the area becomes reduced to where it’s not a special place, then the boats aren’t going to come there anyway,” Patel said.

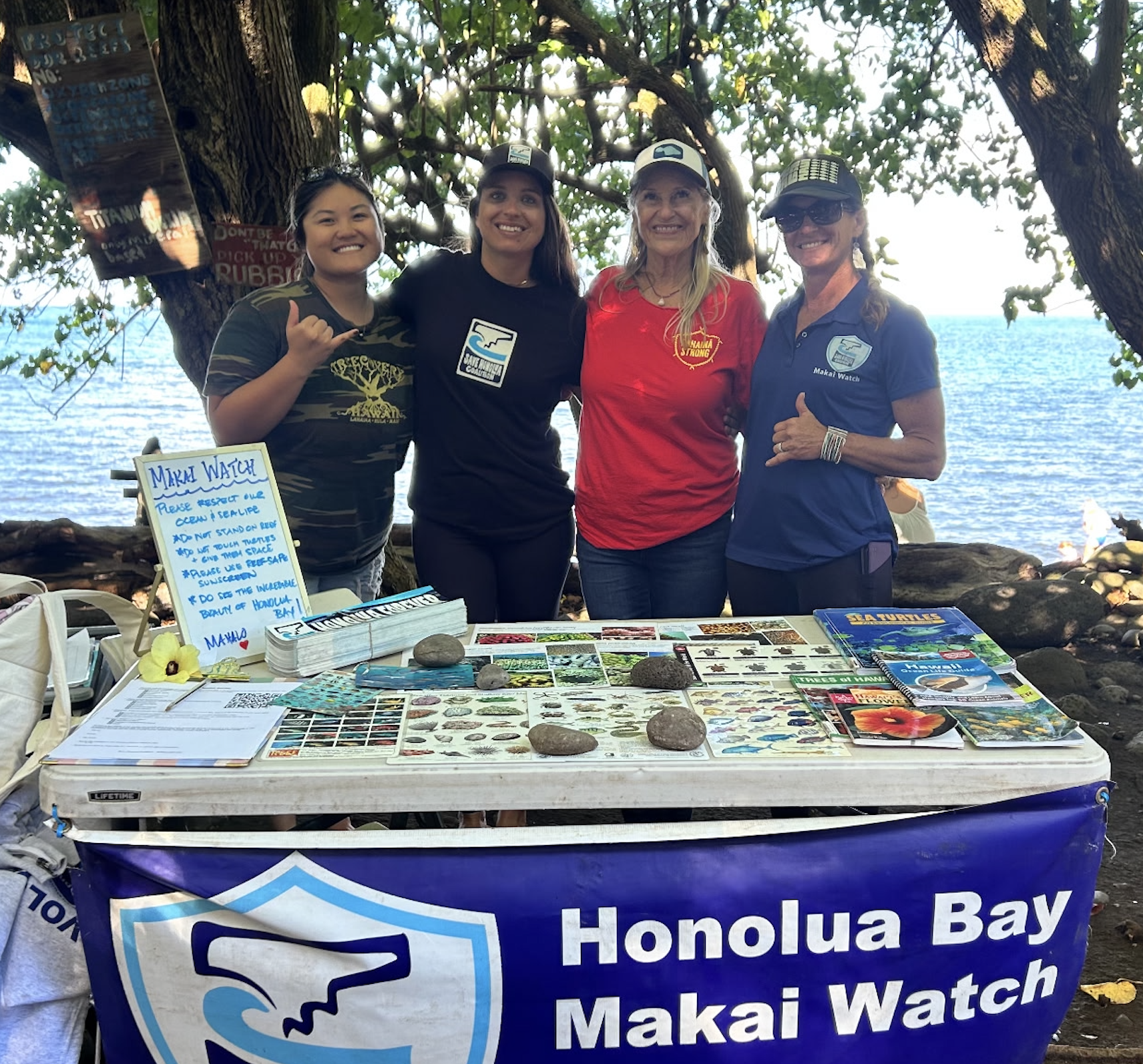

Last year, as tourism started to pick up again, Save Honolua launched its own branch of Makai Watch, a statewide program of volunteers who serve as the “eyes and ears” for the environment. Beltz said they’re trained to educate the public, protect marine life in distress and report violations like boats or swimmers harassing dolphins.

Save Honolua got two grants totaling $50,000 to pay for four part-time staff, Carty said.

Team members are posted at the bay five days a week during peak hours, usually around 9 a.m. to 2 p.m. They keep track of visitor numbers and teach people to keep a safe distance from marine life, avoid stepping on coral and use reef-safe sunscreen. Beltz recently trained to be a scientific diver with Kuleana Coral and hopes the team can start regularly documenting the status and health of the reef.

“I think it’s really special to kilo (watch closely) and to observe the same environment day to day,” said Beltz, who started her job in February 2024. “We all have a connection to that place. I think it’s been overlooked for too long.”

Beltz said she approaches visitors with kindness, because some people simply don’t know the right practices. But even with the signs and in-person education, not everyone listens. Kiakona said some have been caught urinating on burial sites and leaving behind toilet paper. Carty even started his own port-a-potty business, “Big John,” to keep people from going in the bushes.

Kiakona said “we need to start prioritizing our place.”

“The health of this ‘āina … determines the health of its people,” Kiakona said. “The health of its people determines the health of the economy.”